You know what’s awesome about freelancing? Almost everything. Pants are optional (mostly), pets make better coworkers than most people, and you can listen to Kenny G as loud as you like without fear of mockery or reprisal from colleagues. (Ahem.)

Know what sucks about freelancing?

Paying taxes.

If you’re thinking of striking out on your own as a freelancer or launching your own business, you and you alone are responsible for making sure Uncle Sam gets what he’s owed.

Unfortunately, the U.S. taxation system is one of the most grotesquely complex bureaucracies in the world, and to the uninitiated, filing a simple return as an independent contractor can quickly become a Byzantine nightmare.

Today I’ll be guiding you through the fun and exciting world of taxes for freelancers. We’ll cover some general points before exploring some of the juicier stuff, like what you can (probably) write off as well as pitfalls to avoid. Before we get started, though…

First, A Very Important Disclaimer

Before we go any further, it’s important to note that this guide focuses exclusively on American taxation law; although some of the tips may apply if you live elsewhere, this guide is primarily for freelancers living and working in the United States and may apply to overseas contractors working for American companies.

Abandon hope, all ye who enter here…

I am not a lawyer. I am not certified by any bar association (insert drinking joke here), nor am I qualified to offer legal advice. Also, I am not a personal finance expert. As such, none of the content in this post should be considered a substitute for hiring an accountant or tax attorney who knows what they’re talking about. These are general guidelines only, and should NOT be taken as hard-and-fast rules about what you can and can’t do with your taxes as a freelancer.

Also, please note that for the sake of simplicity, all of the tips and advice below apply solely to federal taxes, i.e. money that you owe to the federal government. State tax law varies widely from one state to another, the complexities of which would obviously be impractical to get into here.

Pretty much.

If you are in any doubt whatsoever about any of the issues raised in this post, contact the IRS (or your state’s treasury office). Contrary to common misconception, most of the people who work for the IRS are actually really awesome, friendly, helpful people. Don’t be afraid to contact them directly if – and when – things get obscenely complicated.

Also note that the terms “freelancer” and “independent contractor” will be used interchangeably throughout the post, despite the fact that there are subtle differences.

With that out of the way, let’s get down to business. See what I did there?

How Do Taxes Work As a Freelancer?

The biggest difference between paying taxes as an employee and a contractor is that your taxes are usually withheld by your employer before you get your paycheck, whereas freelancers are on the hook for setting taxes aside themselves. We’ll get to more on this shortly.

Not sure what kind of savings account is right for you? Why not cram

your money into a Mason jar instead?

Another major difference is the actual rate of tax you’ll be expected to pay. This will change depending on how much you earn, as well as the deductions for which you’re eligible.

Basically, virtually every aspect of paying taxes as a freelancer depends on dozens of variables and personal circumstances. Awesome, right?

Not really.

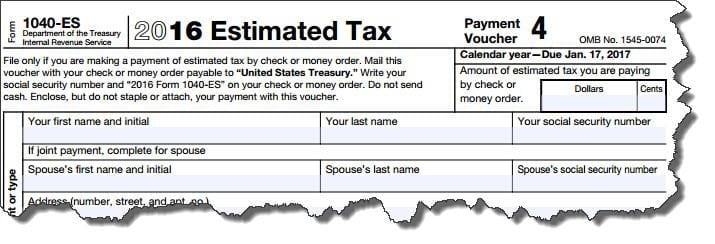

Paying Quarterly Estimates as a Freelancer

Remember when we talked about how freelancers are on the hook for setting aside money to pay their own taxes?

Most independent contractors and self-employed individuals are expected to pay what is known as quarterly estimates to the IRS four times per year. I say “most” because – helpfully! – there are some exceptions.

For example, if you’re expecting to owe less than $1,000 in taxes for the fiscal year after income tax withholding (income that is subject to automatic withholding of taxes, such as salaried earnings), you don’t need to file quarterly estimates. Similarly, if your income tax withholding meets or exceeds 90% of your tax liability for that fiscal year, you don’t have to make quarterly estimate payments. For more information on requirements for quarterly estimates, check out this post at the TurboTax blog.

Quarterly estimates are exactly what the name implies – an estimate of how much tax you owe, paid once per quarter. However, you can’t just send the IRS a check whenever you like. There are clearly defined deadlines for quarterly estimate payments, and each payment period has its own payment due date:

| Payment Period | Due Date |

|---|---|

| January 1 – March 31 | April 15 |

| April 1 – May 31 | June 15 |

| June 1 – August 31 | September 15 |

| September 1 – December 31 | January 15* of the following year. *See January payment in Chapter 2 of Publication 505, Tax Withholding and Estimated Tax |

| Fiscal year taxpayers | If your tax year doesn’t begin on January 1, see the special rules for fiscal year taxpayers in Chapter 2 of Publication 505 |

| Farmers and fishermen | See Chapter 2 of Publication 505 |

As the IRS page on quarterly estimates states, even if you end up being owed a refund at the end of the fiscal year, you’ll still be penalized if you miss these payment deadlines. Late fees will also vary depending on how much you owe and how late your payment is.

I’m not your mom, so I’m not going to tell you how to run your business. All I’ll say is that personally, I find maintaining two separate checking accounts works best; one for “regular” stuff like food and shelter and other things in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and another solely for quarterly estimates.

What Can I Write Off as Tax Deductions as a Freelancer?

A few years ago, I read an amazing story on a message board about an attorney who worked in Baltimore, Maryland. In addition to his regular office, this guy claimed to have bought a fax machine, installed it on his modest yacht, and wrote the entire thing – including the boat – off as a tax deduction because the addition of the fax machine allowed him to claim the yacht as “office space.”

My kinda workspace.

Honestly, I don’t particularly care whether the story is true. It could go either way, really. What I love about this story is that people try to pull this stuff all the time, well-intentioned or otherwise. There have been some truly hilarious and bizarre write-offs over the years, many of which were successfully upheld in tax court after initial rulings to the contrary by the IRS. However, knowing exactly what you can and cannot claim as a deduction is tricky.

How Tax Deductions Work for Freelancers

People tend to get excited about tax deductions, and for good reason – but what are they?

Tax deductions are itemized reductions in the total amount of taxable income a person earns in a year.

Let’s say you earn $40,000 per year and claimed no deductions. In this example, the IRS would expect you to pay taxes on the entirety of that $40,000. Now let’s say that you’re a freelancer earning $40,000 per year and pay for your own private health insurance, which costs $5,000 per year. Because you can deduct (or “write off” the expense, to use a common expression) the entirety of private health insurance costs, this means the IRS would only expect you to pay taxes on $35,000.

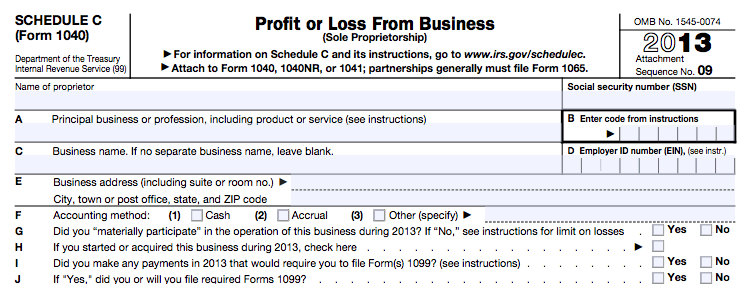

The first thing you need to know about deductions as a freelancer is that most deductions are submitted as part of a form known as Schedule C Form 1040.

Schedule C Form 1040 in all its glory

As with virtually everything relating to the American taxation system, there are few hard-and-fast rules regarding deductions – almost everything has caveats attached.

Take home offices, for instance. You can write off certain expenses as deductions, but for a home office to be a valid deduction, you need to use your workspace exclusively for business purposes. This means your workspace must be dedicated solely to work; you can’t write off a portion of your mortgage or rent if you work from your kitchen table, for example. Also note that even if you meet this criteria, you can only deduct a portion of your living expenses.

Protip: This isn’t a “home office,” at least as far as the IRS is concerned.

The same principle applies for other business expenses. The IRS allows freelancers and self-employed individuals to deduct up to 50% of meal expenses if they were for legitimate business purposes (think meeting a potential client for lunch), but trying to deduct more than that could flag you for an audit.

Business Expenses That Freelancers Can Deduct

We’ve established that everything with the IRS is conditional and that only some expenses can be deducted – but what, specifically, can you deduct in the first place? Below is a summary of the kinds of expenses you can legitimately deduct as an independent contractor (with relevant caveats).

For the sake of ease, assume that any and all of the costs below are subject to the IRS’ determinations, including the percentage of these costs that can be deducted.

- Travel and accommodation: If you travel for work, you can deduct at least some of your travel and accommodation costs as business expenses. This includes costs related to flights, cabs/ride-hail services, train fares, car rentals, and hotel/motel rooms.

- Meals: As noted above, a portion of meal expenses incurred for business reasons are deductible in many circumstances.

- Website costs: Expenses associated with maintaining your online presence – including website hosting fees and domain registrations – are deductible.

- Vehicle maintenance and mileage: If you use a personal vehicle for your business, you can deduct some of the expenses related to vehicle maintenance such as wear and tear on your vehicle, as well as some fuel costs (typically calculated by mileage). There are two ways to deduct these expenses; a standard mileage option and an actual expense option. The standard mileage option allows you to deduct up to $0.535 per mile, whereas the actual expense option allows you to deduct a percentage of all vehicle maintenance costs, including lease payments, repair, new tires, registration, and insurance, among other costs. For more on the nuances of these expenses, check out QuickBooks’ excellent guide to vehicle deductions.

- Software costs: As a freelancer, it’s likely that you need at least a few software tools to run your business. Fortunately, such expenses are deductible. This can apply to the outright purchase of one-off licenses as well as subscription-based programs.

- Utilities: Similarly to home office-related expenses, certain utility costs can be deducted if you work from home. Electricity, phone bills, broadband access, and other utilities can be written off (in part) depending on your circumstances.

- Unpaid invoices: Every freelancer I know has at least one horror story of a client that outright refused to pay. Although this is one of the most infuriating aspects of working for yourself, the IRS does sympathize and allows independent contractors to write off unpaid invoices as lost income. Also, it’s amazing how many freelancers I run into who don’t know this.

- Healthcare coverage: There’s no getting around the fact that, for all the political rhetoric about “freedom of choice,” searching for and buying private health insurance coverage as a freelancer sucks. Fortunately, you can deduct the entirety of your privately purchased health insurance premiums on your taxes. Note, however, that you cannot deduct health insurance premiums if your insurance is provided through your spouse’s employer.

There are plenty of other things you can deduct, such as retirement contributions (ha), legal fees, and professional development expenses such as training programs and educational courses, to name a few. If in doubt, talk to a qualified tax professional.

What Happens If You Don’t Pay Your Taxes as a Freelancer?

Now that we’ve looked at paying quarterly estimates, deductibles, and what proposed tax reform could mean for independent contractors, it’s time to ask the most scary question of all – what happens if you don’t pay your taxes as a freelancer?

Maybe don’t go DIRECTLY to jail…

Firstly, remember when we talked about quarterly estimate payment deadlines? Well, if you miss these deadlines, the IRS will apply late payment fees and interest on your total tax liability for that fiscal year i.e. the total amount owed. These fees will be levied against you even if you successfully filed for an extension, so don’t assume that applying for an extension will spare you from late fees – it won’t.

There are two main types of penalties that the IRS applies:

- Failure to file – a penalty applied if you fail to file a tax return for a particular fiscal year

- Failure to pay – a penalty applied if you file a return, but fail to pay, your tax liability for a particular fiscal year

According to the IRS, the penalty for filing your return late is typically 5% of the unpaid tax owed per month. This penalty begins to accrue on the day after the filing deadline, and will not exceed 25% of the total tax liability owed.

It’s funny because it’s true!

Failure-to-pay penalties are typically 0.5% of your unpaid tax liability. Similarly to the failure-to-file penalty, penalties for failing to pay your taxes by the due date begin to accrue the day after the payment deadline, and applies to each month or partial month that taxes are owed.

As we’ve established, there are few hard-and-fast rules when it comes to taxes. If you’re due a refund, for example, penalties for late filing or late payments will usually be deducted from your refund. Similarly, there are certain circumstances that might mean you won’t be subject to penalties at all. Again, if you’re not sure, contact the IRS directly or speak with a qualified tax professional.

Entering into Payment Agreements with the IRS

So you’ve filed your return (late or otherwise), calculated your liability, and – to your horror – have realized that you owe more than you can pay. What now?

One option that may be available to you is entering into a repayment agreement with the IRS. This type of agreement allows a taxpayer to repay their tax liability from one or more previous fiscal years on a monthly basis. Payments can debited directly from a bank account, making it easy to repay your owed taxes regularly and without having to worry about mailing checks every month.

Although the IRS is generally very forgiving when it comes to repayments, there are some eligibility requirements for taxpayers hoping to enter into a repayment agreement. Check the IRS website for details on eligibility and how to apply.

Make an Offer-in-Compromise

Another option for repaying back taxes is making what is known as an “offer in compromise.” Basically, this is an offer to make a one-time, lump sum payment to the IRS that is typically lower than the total amount owed. For example, you could make an offer-in-compromise to pay $6,000 on a tax liability of $10,000. However, offers-in-compromise can be spread out over several payments as part of what the IRS calls “periodic payments.”

Unfortunately, there’s a little more to it than this.

It’s important to note that the IRS doesn’t have to accept an offer-in-compromise. If the IRS determines that you have the means to pay via an installment agreement, it will usually insist on this arrangement. In addition, the IRS may pursue other collection actions before agreeing to an application for an offer-in-compromise.

Read more about offers-in-compromise at the official IRS website.

Declare Bankruptcy

This may be an option when all hope seems lost, but it should be considered the nuclear option.

Chapter 13 is the most common type of bankruptcy for taxpayers who cannot repay their tax liability. However, filing for Chapter 13 is a last resort for all parties involved – including the IRS.

Try not to end up here.

Even if you don’t care how declaring bankruptcy will affect your financial future, there are several clauses that taxpayers must meet before filing for Chapter 13:

- Taxpayers must have filed returns for ALL tax periods for four years prior to filing Chapter 13

- During bankruptcy proceedings, taxpayers must continue to file (or apply for an extension) for all applicable returns expected

- All current taxes must be paid while a bankruptcy case proceeds through the courts

- Any failure to file the expected returns and pay current taxes owed may result in the case being dismissed

Again, this is not a decision to be made lightly. Filing bankruptcy is a big deal, especially in today’s society when virtually every metric of your perceived worth is tied to your credit score. If there’s really no other option, though, it may be worth considering. If you’re thinking about it, talk it over with a tax attorney first. In fact, if you’re thinking about doing anything mentioned in this post, talk to a tax attorney first.

Helpful Tax Resources for Confused Freelancers

We’ve barely scratched the surface of how potentially complex it can be to navigate taxation as a freelancer. To help you figure things out, here are some useful resources that you may want to check out:

- US Tax Center at IRS: This IRS website offers a ton of information on virtually every tax-related topic you can think of, and the site is significantly easier to navigate than the main IRS site.

- Freelancer’s Union: Although this non-profit organization is based in New York City, the Freelancer’s Union has some really excellent advice for self-employed individuals, and makes complex topics accessible and easy to understand.

- Reddit: I know, I know, Reddit can be a five-alarm dumpster fire of online toxicity, but the /r/personalfinance and /r/tax subreddits can be valuable sources of information if you ask the right questions (and do a search of previously asked questions before asking your own, per the unspoken galactic laws of Reddit). As with everything else in this post, any and all advice you may receive from well-meaning redditors should NOT be taken as binding legal or financial advice, even if that person claims to be a lawyer or certified accountant.