Nobody actually knows anything about SEO with 100% certainty.

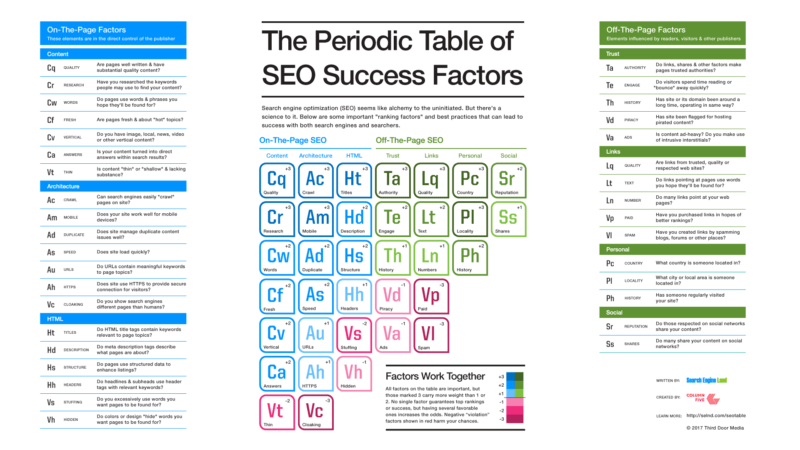

There are ~200 ranking factors. We think. Give or take. Links, content, and RankBrain top the list. We infer.

But never, ever, ever, does Google come out and say, “Here’s exactly what you should do. Step 1, Step 2, Step 3.”

The deck is also stacked against most of us. The algorithm (we think) rewards well-known brands. Things like frequent brand mentions, “high-quality” backlinks, and amazing content.

New or underfunded? Good luck.

Hitting all 16 on-page optimization points you read about on some blog post won’t cut it. Those are table stakes.

Instead, if you want to grow site traffic in a serious way, you need to experiment, do what big brands won’t do, and discover what works best for you (instead of reading someone else’s best guess.)

Ready to get your hands dirty? Here are 7 SEO tests you need to try on your own site.

But first, let’s cover one thing…

How to Run SEO Tests Responsibly

Every marketer worth their salt knows about testing.

You test landing pages to see which one drives a higher conversion rate. You test offers to see which ones result in more leads. You test headlines to see which brings in more readership. You test your button colors. (Even though they don’t do anything in the long run.)

And yet, SEO?

“Meh. Just sprinkle some keywords on this page before it goes live, please.”

Obviously, that’s not ideal. It’s not even good. It’s mediocre at best.

We’re not in this for mediocre. Your competition isn’t mediocre. They’re spending 2x on this stuff. In response, you need to be running tests for SEO.

First, check out Rand Fishkin’s advice for running successful SEO tests. Then follow these simple steps:

- Experiment vs. control: You’d never, ever, ever change every single headline on all landing pages for paid campaigns. So don’t do it organically, either. You tweak a single element and run it against the control group to limit your risk.

- Segmentation: Similarly, you’d never throw up a new landing page for each paid campaign. Instead, you’d pick one keyword. One campaign. Or 10% of the traffic. Again, you’d use a much smaller-than-usual segment to control variations.

- Repeatability: Got some decent results? Good. Do it again. One-time blips won’t pay the bills.

Point is, proceed with caution on this stuff. You don’t want to do something you can’t undo. You don’t want to de-index your site if you don’t know exactly how to roll back those changes.

Now, roll up your sleeves and get ready to run some SEO experiments.

1. Remove bold tags

Keyword density used to be a thing. You wanted to place oh-so-many keywords into a piece to hit the 1-2% that guaranteed nirvana.

Keyword stuffing quickly became a thing, too. (In fact, it still works on YouTube.)

The theory is, if a little of something works, a lot of something will kill.

Fast forward a few years, and we’re still going for the same tricks. For example, bolding keywords.

You know, try to work them into the H2 if you can. Then slap at least a few bolds on before they go out the door. This sounds silly. It can’t work… can it? Because it starts to look ridiculous, too.

Turns out, one SEO experiment showed that, unsurprisingly, being overzealous with <strong> tags can backfire.

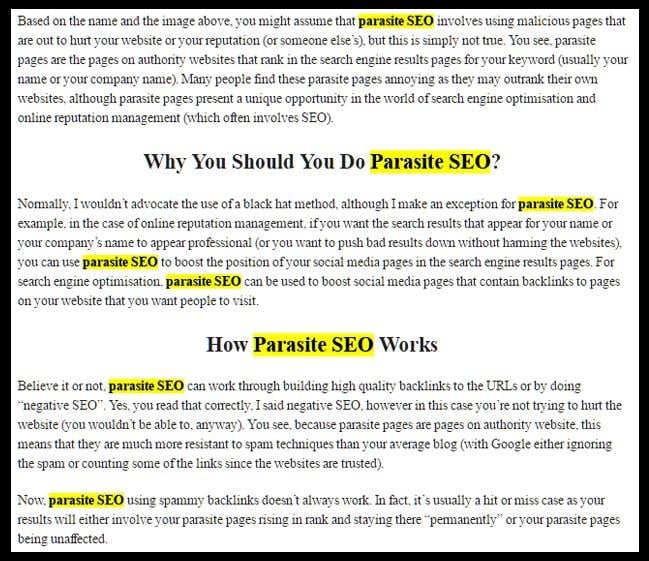

Alistair Kavalt at Sycosure decided to put this to the test after reading about it from SEOPressor. Here’s what happened: On September 7, 2016, Alistair decided to add bold tags to primary keywords on the following page. Take a wild guess at what that keyword was:

Looks like About.com, right?

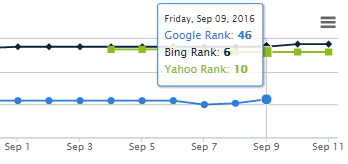

He made these changes to just a single page on the site and used a combination of manual rank checks with SerpBook to see how results would fluctuate.

Alistair didn’t have to wait long. Only three days later, the page “dropped 53 positions,” virtually disappearing from the SERPs for “parasite SEO.”

A few days later he’d had enough. He removed the bold tags and again waited to see what (if anything) would happen.

On September 17, one week after disappearing from the rankings and only a few days after removing the bold tags, the page shot back up to the first position for “parasite SEO.”

The page eventually settled back down, but the implications were clear.

Bold tags do matter – but not quite in the way you’d think. If you’re still bolding keywords on a lot of your pages, try removing those bold tags and see what happens to your rankings.

2. Strip dates from URLs

Chances are, you created your blog years ago. Before you knew what you were doing – or maybe your business started it before you were even around.

The bummer is that decisions made back then can (and often do) come back to haunt you today.

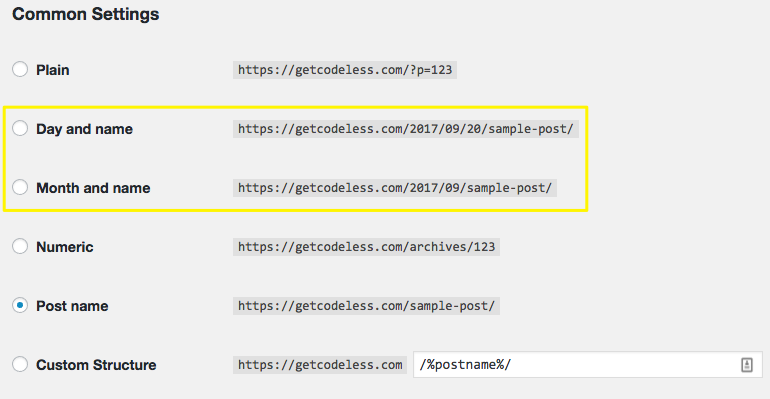

Take permalinks. It’s normal to assign a custom permalink structure in WordPress when you’re first getting started.

For example, select one of the following, and you’re stuck with dates in your URLs for good:

The reason? Changing permalink settings later would cause mass 404 errors to ripple throughout your site. It would be like SEO suicide unless you knew exactly what you were doing (and how to fix it).

So. What, exactly, is the optimal permalink structure? Are dates in the URL good or bad?

Harsh from ShoutMeLoud decided to find out. Initially, he claimed that “removing dates had a positive impact on the overall search engine ranking.”

Then he tested it.

The reasoning here comes back to content relevancy. Some of his old blog posts dated back to 2008. The content was evergreen. It was still legit. But anyone seeing that “2008” in the URL string would immediately question its validity.

So he experimented with both approaches: date and date-less (like me in high school) blog posts.

Adding dates turns out, only drove down his traffic:

Removing the dates caused rankings and traffic to come back up:

One potential hypothesis comes back to SERP click-through rates. Outdated content inevitably looks outdated.

If you see two equally compelling results, all other things being equal, you might skip over the old one in favor of the new:

Removing dates from your post metadata is usually fairly easy. You might need some technical help, but it’s usually just removing a line of code from your site or theme.

When removing dates from your permalinks, proceed with caution. Make sure you know your way around redirects.

3. Optimize for dwell time

Originally introduced by Duane Forrester, previously of Bing, dwell time refers to the length of time a visitor spends on a page before heading back to the search engine that sent them there. (We all know it was Google. Sorry Bing.)

Ideally, the longer the dwell time, the better.

It makes perfect sense when you think about it.

SEO isn’t about rankings, keywords, etc., contrary to popular belief. It’s about answering search queries. It’s about being the best at giving people what they’re looking for.

Your goal is to match search intent.

Someone hitting your site and then the back button seconds later would result in a low dwell time. And it’s a bad sign that you haven’t been able to give them what they were looking for.

So it’s kinda like the Bounce Rate or Time on Page you’re already used to. But not really. A little more nuance is involved.

Dwell time is an important concept because it dictates how we should design pages and what should go on them. It’s why long-form posts tend to rank better than short-form ones – not because people like reading (they don’t), but because it helps keep people glued to your screen a little longer.

Yeeeears ago (one e for each year), Dan Shewan at WordStream pointed to two different examples that suggest Google can measure your dwell time.

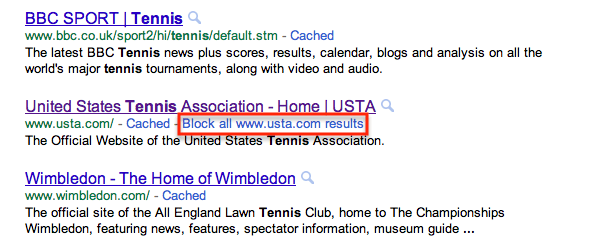

The first was the option for visitors to block results from a specific domain:

And the second is the reverse: the ability to get more content from that source.

Since then, we’ve had several more studies come out confirming that dwell time does have some sort of impact on rankings.

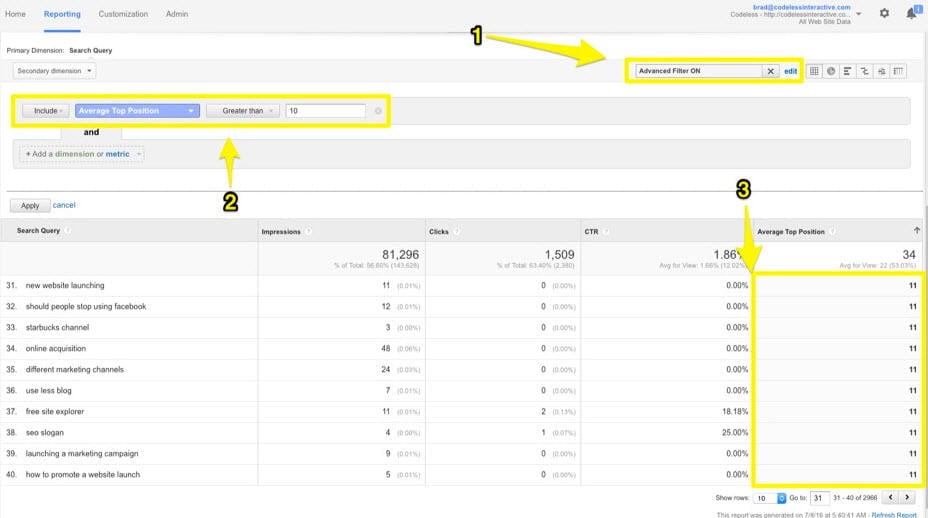

Testing this one can be relatively easy. Start by improving the content. Take a post that ranks well, but not that well. Think, “top of the second page.”

Look for evidence that it’s not quite meeting the searcher’s intent, like high bounce and exit rates with low time on the page.

Then do nothing but improve content quality.

- Update the stats.

- Enhance readability and scannability.

- Add new sections.

- Upgrade the visuals.

- Insert a table of contents to help people jump around.

- Use audio or video to better summarize the page information.

- Include internal links for related articles to create ‘webs’ of content.

Now, monitor results.

4. Prune your site

Bigger is better. More pages = more traffic. Right?

Not exactly. Counterintuitively, less can bring in more, according to one SEO test featured on Moz.

Everett Sizemore makes a case for “pruning” your site by proactively removing stuff that doesn’t enhance quality. Brian Dean has suggested a similar pruning idea.

The theory goes that the less junk you have, the higher the overall quality signal of your site. This would work similarly to AdWords’ Quality Score, giving an indication of how well your ads and campaigns are aligning with users.

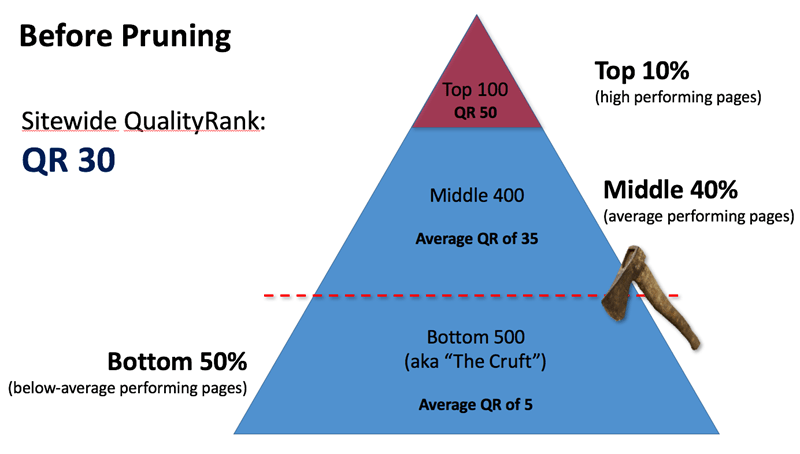

Everett uses QualityRank as a way to explain how this signal works. “Pruning” your low-quality, low-traffic pages increases your site’s overall average score.

For example, you cut the bottom 30-50% of your site’s low-quality content. Now, you’re only left with the middle and upper portions. Fewer pages overall, but killing the low-value pages drives the average page quality up with it.

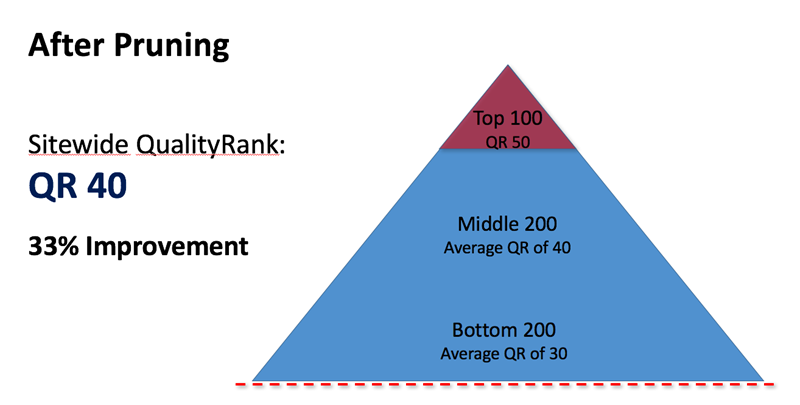

Here’s what that same example would look like after removing the bottom half of their less-than-useful content.

You’ve instantly raised the overall “QualityRank” by ten points without doing anything else. The junk, therefore, was only holding the rest of your stuff down.

Sounds crazy, right?

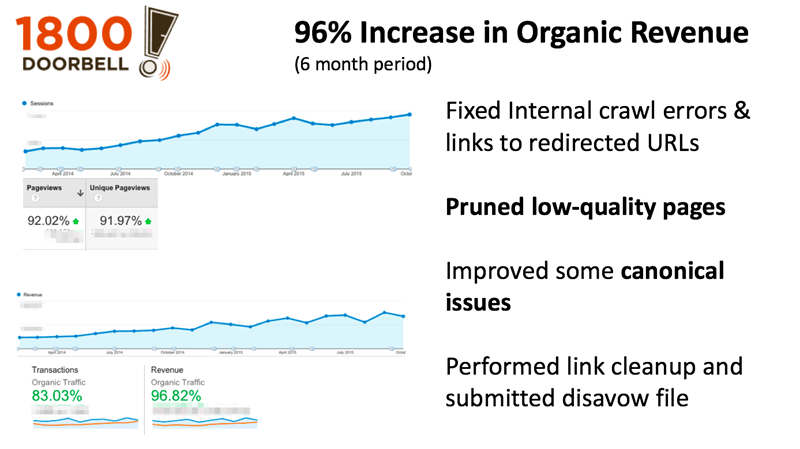

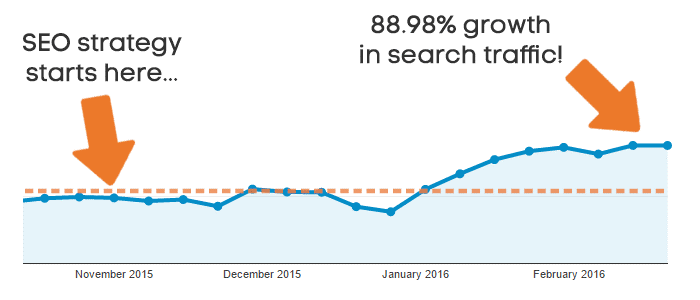

Everett shares a few case studies and examples to prove it works.

First up, 1800doorbell used a combo of technical tweaks + pruning low-quality content to increase revenue from organic search by 96%.

Ahrefs shared their own results of a similar test that showed a massive lift over the course of a year. Again, they placed a big emphasis on pruning (in addition to other technical improvements.)

Everett recommends running a content audit first to uncover your worst performing pages. For example, you can go through to find pages with:

- No organic search traffic

- Ranking > 50

- No backlinks

- No social shares

Removing the content entirely could create unintended consequences and broken links.

Instead, start by just adding a noindex tag on these low-quality pages. That way, they technically still exist on the site – but not from a search engine’s point of view.

>> Get an instant, free SEO and website audit with the LOCALiQ website grader.

5. Don’t sleep on nofollow links

You already know that links matter. You already know that link quality matters.

For example, links from the New York Times are worth more than ones from Bob’s SEO Fairy Dust Farm.

In the same vein, “followed” links are worth more than “nofollowed” ones. (More on the difference between these here.)

Picture blog comments. All of those people spamming their way to get links would be disappointed to find out that many commenting systems automatically “nofollow” their links.

It’s basically a way for sites to tell search engines not to attribute value to those links. (Because they’re leaving spammy comments. In 2017.)

The common thought is that “nofollowed” links are completely useless when it comes to SEO value. However, that might not always be the case. Those comment spammers might be onto something (God help us).

Rand and his rag-tag IMEC Lab group confirmed this suspicion in a series of tests.

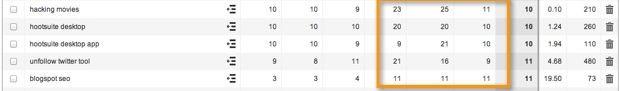

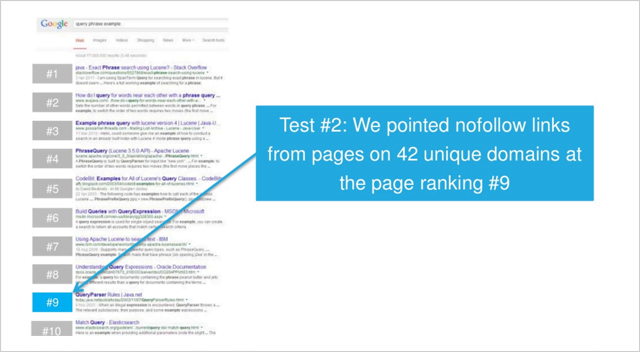

Forty-two nofollow links were pointed towards a page ranking in the ninth position for a “low competition query.”

So what happened?

The page started climbing to the sixth position after those links were indexed.

Removing the nofollow tags on the links helped the page rise to the fifth position.

This experiment suggests that at least for queries that aren’t super competitive, nofollow links aren’t as useless as previously thought. And it does give some credence to the idea that, “the more links, the better.”

6. Improve site loading times

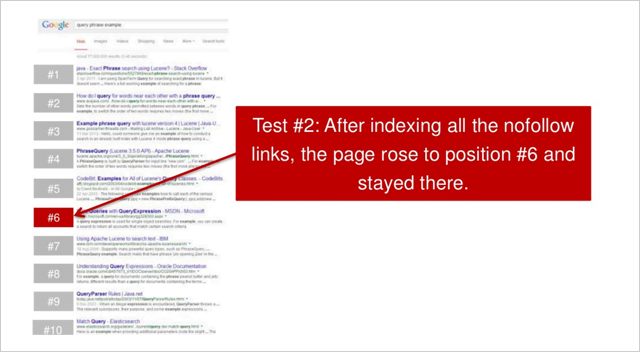

Google released a mobile page speed industry benchmark report in February. Turns out, “The probability of someone bouncing from your site increases by 113 percent if it takes seven seconds to load.”

People really, REALLY don’t like waiting around for pages to load. Especially on mobile devices.

The problem is that the same report found that most mobile pages take three times that longto load (22 seconds.)

Slow page loading times have a trickle-down effect. The longer a page takes to load, the less traffic, more bounces, and less conversions you’ll see.

“Similarly, as the number of elements—text, titles, images—on a page goes from 400 to 6,000, the probability of conversion drops 95 percent.”

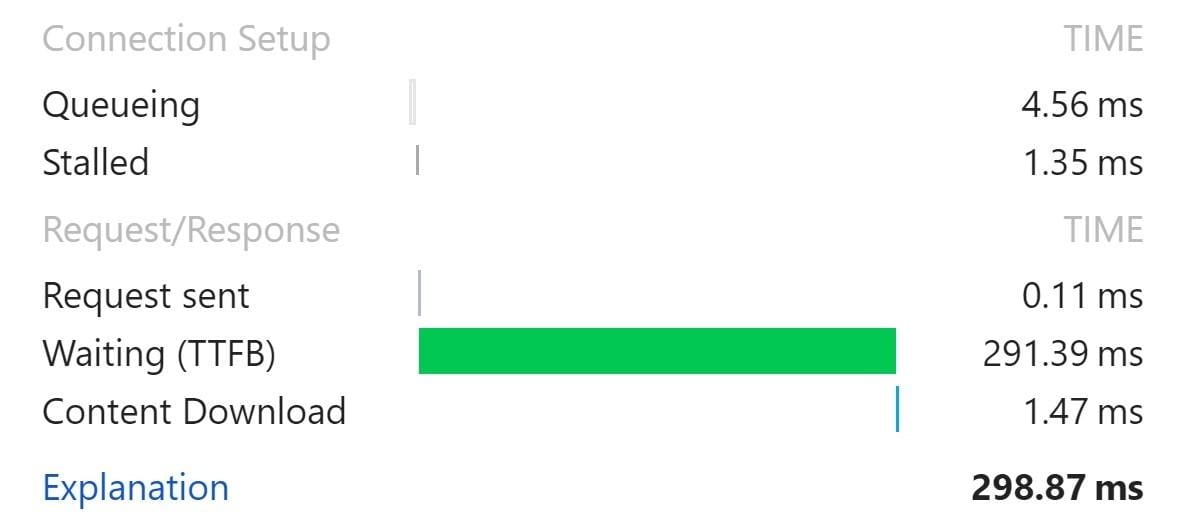

It’s not just the page loading time that drives worse performance. It’s something a little more geekily referred to as Time to First Byte (TTFB).

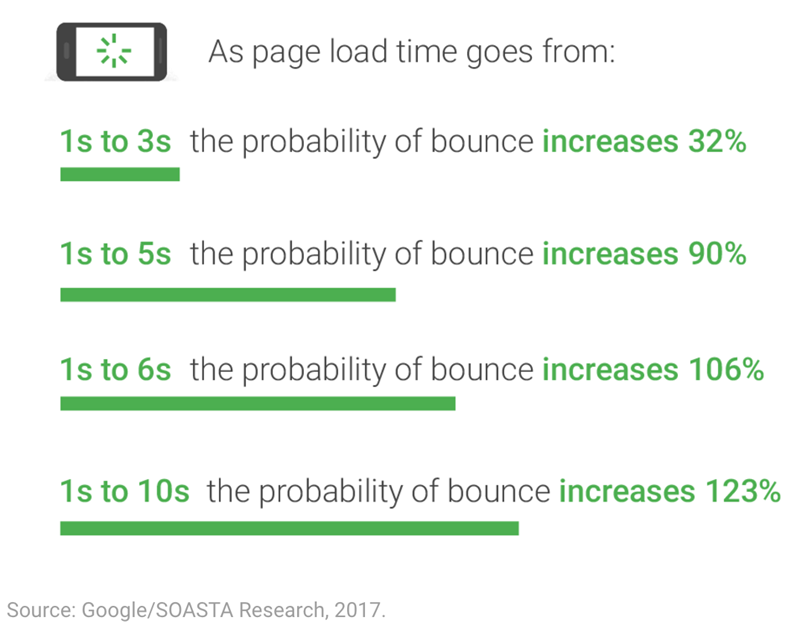

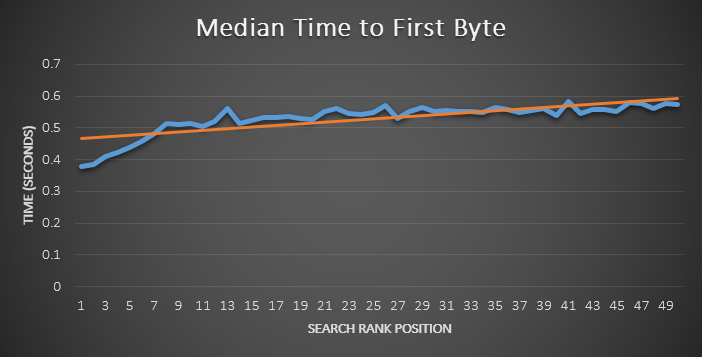

Billy Hoffman worked with Moz years ago to run an experiment. They collected 100,000 pages to evaluate. They then used 40 different page loading metrics to base their analysis.

They then recorded the median page loading time based on average search position to see if there was any correlation.

In other words, they expected to see better-ranking pages have a lower average page loading time. But that wasn’t always the case.

Instead, they found a much stronger correlation between rankings and TTFB.

The higher a page ranked, the lower its TTFB.

Billy reasoned that “TTFB is likely the quickest and easiest metric for Google to capture,” which can help explain why it seems to be such an influential factor.

Ok, great. That would actually mean something if you knew what Time to First Byte was in the first place.

Basically, it’s the time it takes for search engines to “receive the first byte of data from the server.”

Someone types in your web address and hits “Enter.” That request is sent to your server to send the appropriate data. Your server processes that request. It gathers data from different places and assembles it for transmit. Then it’s sent back to the original client or browser that requested it in the first place.

Now, multiply that sequence, by tens of thousands of visitors, spread across the planet, at all hours of the day. Every additional or redundant issue, like massive image files or poor code, can throw a wrench in this process. Even a bad WiFi connection can slow it down.

In other words, page loading isn’t the only issue to be aware of or test. Delivering relevant content, faster, is too.

That’s why using a Content Delivery Network can help. It both speeds up page loading times and lessens the initial load that’s transmitted each time someone requests content from your site.

Keep on testin’

PPC is fairly transparent in comparison to SEO. You know how much keywords cost. Many tools can show you what your competitors are paying or what their ad text and landing pages look like.

However, in SEO, there’s no shortage of myths and urban legends out there.

We can look for best practices to help guide the way. But at the end of the day, we have to test and run experiments for ourselves to really know for sure.

The good news is that you don’t have to start in the dark. You can begin with these six SEO tests that have already worked for others to start finding out what works, and what doesn’t, for you.