The performance-based advertising world is focused on CPA. For those who are not aware of the acronym, it means cost per acquisition or cost per action (both versions are used). An acquisition or action can be anything that a website’s owners want it to be: a confirmed sale or a lead generated, or a registered user or downloaded application. Any discrete action that can be tracked as the result of paid search or any other type of performance-based marketing is a CPA. Many marketers obsess over the profitable value of a CPA to their business. This is a worthwhile undertaking since knowing your monetary targets in paid search is the easiest way to hit them. Let’s take a simple example for context.

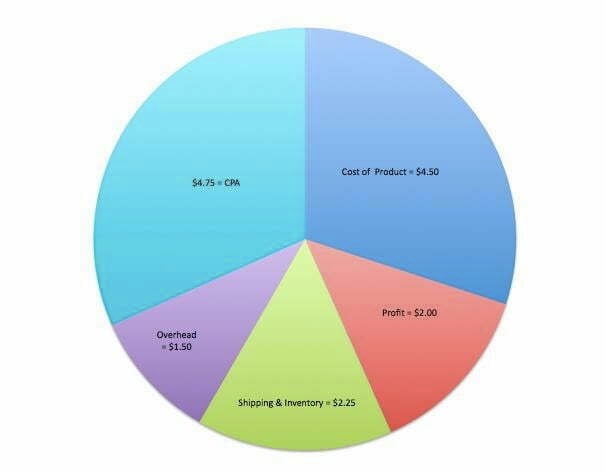

Say you’re selling baseball hats online. For the ease of the example, we’ll say that every hat is $15.00. You work out your target CPA by figuring out how much you can afford to spend on marketing to sell a hat. Let’s say your cost breakdown looks like this:

$15 for the sale

- 30% for the cost of the product ($4.50)

- 15% for the cost of shipping and inventory ($2.25)

- 10% for the administrative overhead of your operation ($1.50)

This totals $8.25 in costs (we haven’t mentioned sales and marketing costs yet). If you need to make $2/hat sale to have a profitable business, it means you can only afford $4.75 as a CPA ($15 – $8.25 – $2.00 = $4.75). You have to spend less than $4.25 (on average) to build a profitable business.

Of course, every business has a different CPA based on its core product price and the type of CPA we’re talking about. An enterprise software company that sells $250,000 software products might be able to afford $60 or even $100 CPAs (cost per lead) and the math will still work out. Either way, the cost structure will determine what you can spend to sell something in the end (a lead can be thought of as a sale, just a qualifying step or two away).

Many paid-search marketers are laser-focused on managing their campaigns to the target CPA they have. This is wise – it’s debated whether you should focus on the average CPA across all sales or the media or something else.

That said, many businesses have repeat customers. The long-term value of a customer is often called the LTV (lifetime value). LTV is an important consideration in your business because it can dramatically change what you can really afford from a CPA basis.

Let’s use the baseball hat example again. Assume that 50% of your customers actually end up buying a second hat a few months later. Let’s assume that the second time around they just type in your website address (i.e., don’t click on another ad) to make the purchase. In our example, if you spend $4.25 to get that customer the first time and $0 to get them the second time, the actual sales and marketing cost of that customer is really $2.12 per sale. But the other way to think of it is that your CPA is really not $4.25, it’s $6.37. Why $6.37? Well, 50% of your customers buy twice at the same advertising cost. So if your cost per sale for 50% of your customers is $4.25 and your cost per sale for the other 50% is $2.12, then your actual profitable cost per sale is the blending of this. You can afford to pay more for each CPA because you know half of your customers will come back and buy again.

While there is no singular simple way to track LTV – some people do it in Salesforce, some with customer accounts, etc. – it’s an important metric to hunt down and understand. Imagine the lifetime value of an Amazon customer versus the cost of their first sale. They can afford hundreds of dollars of CPAs when they take a multi-year view on their customers’ purchases.

So my recommendation to you is to do some basic work to understand LTV in your business. And then go back to your paid-search targets and make sure you’ve adjusted them. The beauty of realizing you can afford a higher CPA is being able to drive more volume. The old adage applies: You can have as many customers as you like, if you’re willing to pay anything for them.

Niel Robertson is the CEO of Trada.